Municipal Math: Breaking Down Smithville's Debt

By Kristen Meriwether, Publisher

With a month left until the Smithville City Council must pass their new budget, there are still a lot of unknowns. But one fact will remain, regardless of what priorities get funded:

We will start the new fiscal year on Oct. 1 with at least $7.8 million in debt.

And with the council directing the city manager to look into a $3 million tax note for the new fiscal year, and talks of a bond election in May (which may also feature a bond from the school district), that debt number is likely to grow.

So how did we get here? What is all the debt going to pay? Should we borrow more?

Get out your calculators Smithville, it’s time for another Municipal Math story.

What is Smithville’s Debt Funding?

Cities typically use debt to fund a mix of essential big-ticket items, like a new bridge or park, as well as smaller items like police cars and forklifts. Cities in financial trouble can also use debt to cover operating expenses.

There are three ways municipalities typically borrow, and we’ve included what each can fund, if it requires voter approval, and the use and payback timeframe in notes at the end of this article:

1. Tax Notes

2. Certificates of Obligation (COs)

3. General Obligation (GO) Bonds

Smithville’s debt is in both the General Fund and the Utility Fund and is paid off through a variety of ways:

- I&S portion of your city property tax bill: The current city-portion of your property tax bill is $0.58 per $100 valuation. Of that, $0.23 (39%) goes to debt.

- Fee: Your current utility bill has a $5.75 “Water/Wastewater Imp” fee. That is helping to repay the $4.5M CO Smithville took out in 2019 for emergency repairs of the water tower and to make wastewater upgrades. It will not be paid off until 2038.

- Budget: In the General Fund expenditures, there is a section called debt service where funds are budgeted every year to make debt payments.

The City of Smithville currently has five series of debts:

1. Series 2007 CofO

Fund: Utility

Amount: $4.5M

Total debt with interest: $6.7M

Pay off date: November 2027

Reason for debt: To acquire a wastewater treatment plant and for constructing, improving, and extending the city’s wastewater utility system; paying for fees associated with the project

2. Series 2019, Combo tax and limited pledge revenue CofO

Fund: General and Utility

Amount: $2.9M

Total debt with interest: $4.1M

Pay off date: February 2033 for General Fund, February 2038 for Utility Fund

Reason for debt: water and wastewater, street improvements, drainage improvements, supplies, equipment, landscaping, land for right-of-way, fees associated with projects

3. Series 2021 Tax Note

Fund: General and Utility

Amount: $785,000

Total debt with interest: $812,238.65

Pay off date: February 2028

Reason for debt: Machinery (asphalt zipper, brush chipper), police cars, police radios, general street improvements, fees associated with projects

4. Series 2022 Tax Note

Fund: General and Utility

Amount: $1.3M

Total debt with interest: $1.4M

Pay off date: February 2029

Reason for debt: expansion of City Hall, animal control, public works, municipal airport, city vehicles, heavy machinery, street improvements, landscaping, financing and fees associated with projects.

5. Series 2023 Tax Note

Fund: General and Utility

Amount: $2.915M

Total debt with interest: $3.5M

Pay off date: February 2030

Reason for debt: facility improvements (roof repairs, security systems, video surveillance, HVAC), road repairs, patrol cars, chipper, truck, bucket truck, fire truck, playground equipment

Is our debt too much?

It depends on who you ask and what metric you choose to use.

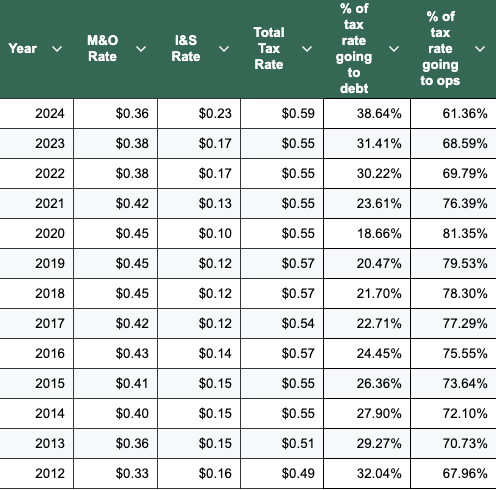

Taxpayers' most direct metric is the I&S portion of the city-portion of their property taxes, which is specifically used to pay for debt. Here is a chart of the tax rate, by year, with both portions (the M&O pays for operating costs), and the % change.

Since 2012 Smithville has averaged 25% of property taxes going to debt. But with $5M in new debt being taken out since 2021, we are now up to 39% of taxpayers' property taxes going to debt, leaving less for general operating expenses.

We asked City Manager Robert Tamble what impact the more than doubling of the I&S rate has had on the city’s ability to use the general fund to pay for operating costs.

“The General Fund has always been challenged from a revenue standpoint,” he said at an interview at City Hall on Tuesday. “In fact, to overcome that deficit, we have to do a $1.1 million transfer from the utility to fund the general which is for the services that people have come to expect.”

He said they’ve tried for years to decrease that transfer, “but something comes up, and we just don't make budget, and you have to provide the services.”

As they’ve taken on more debt since 2019, the city positioned themselves to increase revenue with five housing developments (210 homes), an industrial park near the airport, and a truck stop on Highway 71. But a variety of roadblocks have caused those projects to not come to fruition, leaving what Tamble estimates is $40-50 million in assessed values off the books on the property tax side, and an unknown amount on the sales tax side.

“It's so close, but we're not quite there. And so the seeds we planted four years ago are about to sprout, and the seeds we plant now will take three to four years to sprout,” Tamble said. “It's a constant challenge to balance the needs of the community.”

There are no laws dictating how much debt a city can take on, but the Government Finance Officers Association recommends that debt service should not exceed 10–15% of general fund revenues or expenditures to maintain fiscal health and credit ratings.

We crunched those numbers using the financial audit of last year’s budget.

Debt services were $938,758.

- Debt service as % of general fund revenues ($5.4M) = 17.5%

- Debt service as % of general fund expenditures ($6.8M) = 13.9%

If we use total governmental funds, which includes grants and capital project funding:

- Debt service as % of total government revenues ($8.8M) = 10.6%.

- Debt service as % of total government expenditures ($12.8M) = 7.3%

We asked Tamble which method they used and he said he wasn’t familiar with this recommendation, preferring to ensure they are following laws like the one requiring three months operating costs in the general fund.

“What we look for is do we have any material findings? Are we managing the budget within our means? What's our bond rating?” Tamble said, noting in 2023 it was AA-minus.

“They're not going to give us a tax note if we can't,” Finance Director Cynthia White, who was also at the interview, added.

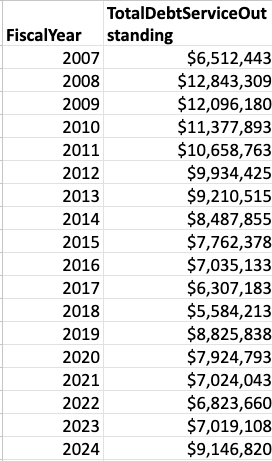

We asked Tamble what his “red line” for debt was and he said he is not a fan of debt, noting it was $11 million when he joined the council and over $9 million when he became city manager in 2013. To his credit, the city did an outstanding job paying down debt through 2018, taking it down to $5.5 million.

Emergency water tower repairs necessitated a $4.5 million C of O in 2019, and the city took out $5 million in additional tax notes between 2021 and 2023 to cover inflationary costs and mounting capital needs, bringing the debt total back up.

“You’ve only got X amount of general revenue, so you've got to come up with revenue from another source,” White said.

Tamble offered to play devil’s advocate.

“If we had done nothing, [then] what? You don't get the streets done. You don't get the wastewater system repaired. You don't get the cop cars,” he said. “You have to look at it all in totality and understand what the needs of the city are. How do you get there?”

We asked Tamble what the city’s strategy for managing debt is.

“Our strategy is to take debt out when and where it's needed,” Tamble said. “Don't be excessive with it and manage it appropriately.”

To Borrow or Not to Borrow

No matter how you slice it, the city does not have enough revenue to cover expenses for this upcoming fiscal year, thanks in part to mostly flat property tax values, and the city’s heavy reliance on the tax as its largest revenue source. The 5% cuts in the first preliminary budget presented last week did not go over well with residents, leading to the realization that taking on more debt is the only solution.

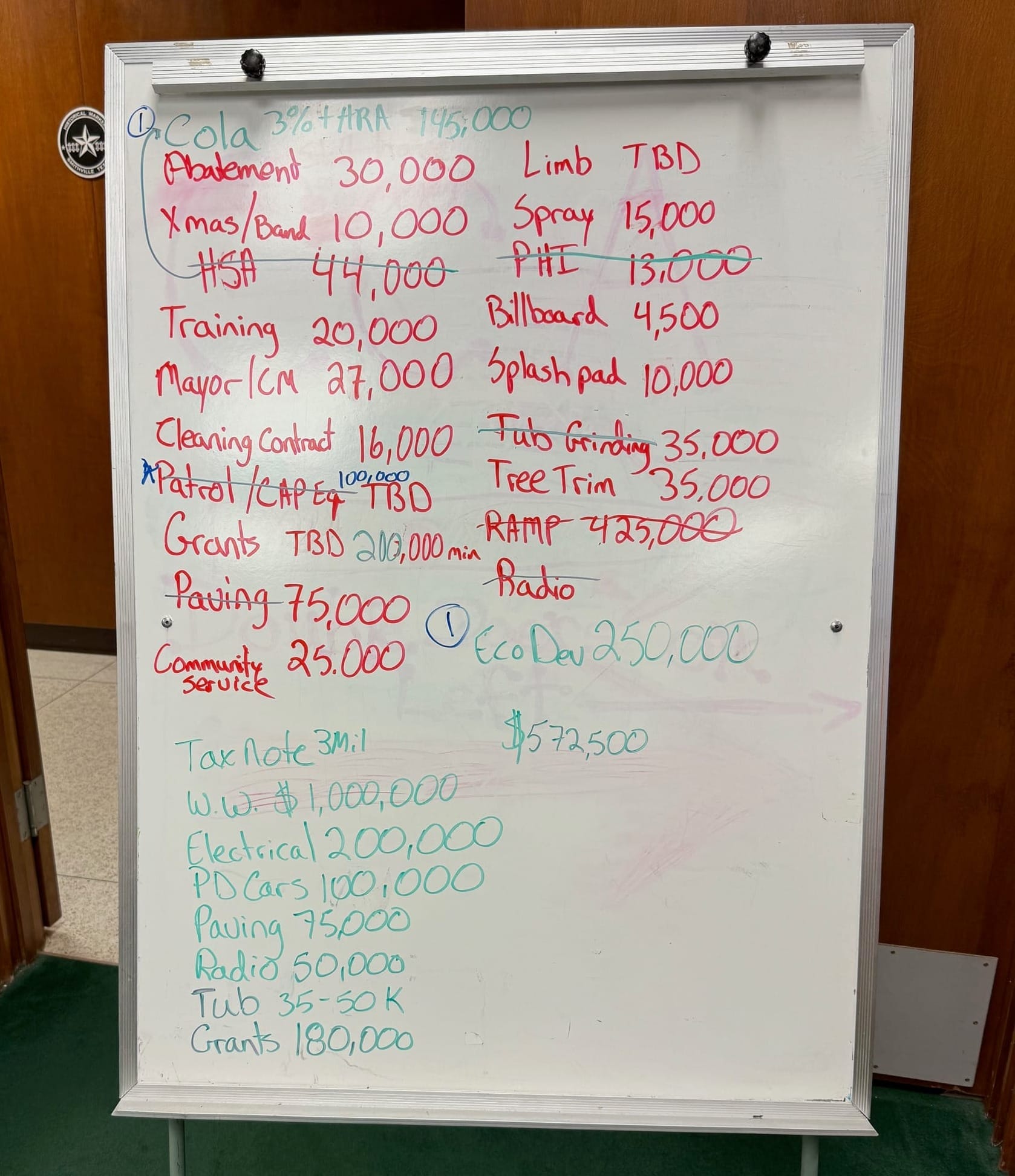

The council created a white board of potential items to put on the tax note including:

- $1 million in matching for wastewater repairs

- $200,000 for electrical repairs for Garwood Park

- $100,000 for police cars

- $75,000 for paving

- $50,000 for radios for the fire department

- $50,000 for tub grinding at the brush dump

- $180,000 for grant matching

The idea behind putting these eligible items to a tax note is to free up money to fund:

- 3% raises for city employees

- Up to $250,000 for an economic development professional

- Services that were cut from the preliminary budget.

While the wastewater repairs and expansion has been a hot topic since the election, there is time if we don’t get the grant, or can’t pass a bond to pay for it.

“We're on a precipice now, where we’ve got to figure out how to fund this wastewater. But the good news is, by law, we don't have to do anything, any design, until we have 75% capacity,” Tamble said when asked about a red line for debt. “So this narrative, we're not getting any growth. Realistically, we don't have to start anything for three or four years. But let's do it now to prepare, get that much further ahead.”

The council will be presented options for tax notes at the Aug. 11 council meeting. The city had a AA-minus rating in 2023 and given their low debt to taxable value percentage, it’s likely they could be approved for up to the $3 million.

You can read how the artificially inflated property values that occurred post-COVID are providing lower numbers, despite a loss in population and negligible new homes in our debt analysis here.

Aug. 1, 4:15pm: Editor's not on the data: We used population data included in the dataset Debt Outstanding by Local Governments which pulls from the Bond Review Board for this story. The City of Smithville emailed after this story was published and challenged the population data in the story. Their data shows:

“In 2000, Smithville, Texas had a population of 3,901 people. The city experienced a 22.1% increase in population between 1990 and 2000, growing from 3,196 to 3,901, according to the Smithville Comprehensive Plan.”

“In 2008, Smithville had a population of around 3,922 people.”

“The 2010 US Census data for Smithville, Texas, indicates a population of 3,817.”

“The 2020 US Census data for Smithville, Texas, was revised/corrected to reflect a population of 4,062.”

We reached out to the BRB to see where they sourced their data, but they have not yet responded. We will update the story as we get more information.

Notes:1. Tax Notes (source: Texas Local Government Code, Chapter 1431, specifically §1431.004 and §1431.011)

- What can be funded: Building public works (like roads or utilities), buying equipment or supplies (like vehicles or materials), covering current budget expenses (like operating costs), paying for professional services (like consultants), or refunding older debts.

- Voter Approval: Not required unless 5% of qualified voters petition for an election within 45 days.

- Timeframes: The money is typically spent within three years and paid back within seven years.

2. Certificates of Obligation (COs) (Source: Texas Local Government Code, Chapter 271, Subchapter C; section §271.045)

- What can be funded: building or improving public works (like roads or utilities), buying land or rights-of-way, purchasing equipment, vehicles, or supplies, hiring professional services (like engineers or architects), or demolishing dangerous structures or restoring historic landmarks. They cannot fund routine budget expenses like salaries.

- Voter Approval: Not required unless 5% of qualified voters petition for an election within 45 days.

- Timeframes: Typically spent within 1–3 years, depending on the project, and paid back over up to 20 years.

3. General Obligation (GO) Bonds (Source: Texas Government Code, Chapter 1331 (Municipal Bonds) and Chapter 1251; Texas Constitution, Article XI, Sections 5 and 7)

- What can be funded:building or improving public works (like streets, sewers, or utilities), constructing or improving municipal buildings, buying land for city purposes, or refunding existing bonds. They cannot fund routine budget expenses like salaries.

- Voter Approval: A majority of voters must approve GO Bonds in an election; there is no petition option.

- Timeframes: money is typically spent within 1–10 years, depending on the project, and paid back over 15–20 years, sometimes up to 30 years.

Comments ()